Knee Pain Explained: Runner’s Knee/PFS

August 23, 2021 The diaphragm is the primary muscle used in the process of inspiration, or inhalation. It is a dome-shaped sheet of muscle that is inserted into the lower ribs. Lying at the base of the thorax (chest), it separates the abdominal cavity from the thoracic cavity.

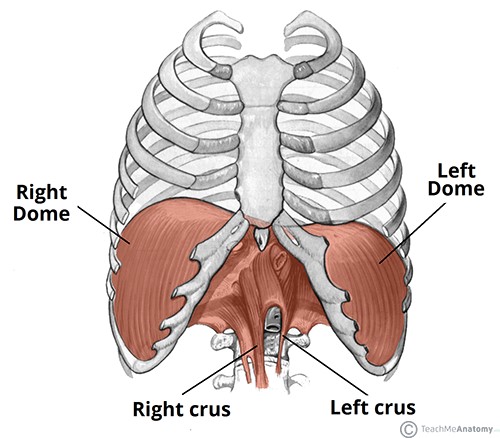

The diaphragm is the primary muscle used in the process of inspiration, or inhalation. It is a dome-shaped sheet of muscle that is inserted into the lower ribs. Lying at the base of the thorax (chest), it separates the abdominal cavity from the thoracic cavity.

The Diaphragm has attachments to both Thoracic (T7-T12) and Lumbar (L1-L3) vertebrae and also attaches to the inner xiphoid process (lower sternum). Therefore it’s not rocket science that if the diaphragm becomes dysfunctional then this can have a great effect on back pain.

When we breathe we never really think about it as an exercise as we just automatically do it, we would never even think that we could breathe incorrectly, I mean it’s just taking air in and out right? What we don’t understand is that breathing is both an autonomic response to living and also a key player in neck, upper / lower back and even hip related pains. That’s right, with breathing dysfunction it can basically affect the whole spine and therefore the muscle structures surrounding it.

Myers discovered several connections that can influence the body when we have dysfunction in the diaphragm, with separate attachments of the crus tendon on both right and left side L1 L2, this means they can act independently of each other and bring issues separately or together. The crus tendon attaches fascially to the anterior longitudinal ligament, it also shares attachments with quadratus lumborum, psoas major and has nerve roots innervated by C3-C5 in the cervical spine. As well as musculoskeletal attachments the diaphragm shares connections with kidneys liver and can affect the adrenal glands and even digestion. That’s a whole lot more than just something to take air in and out the body, in fact it seems like breathing dysfunction can pretty much have an effect on the whole body.

Breathing is automatically driven by our nervous system and like any system this can become lazy, injured or adapt to its environment. When we bend to pick something up we need adequate lumbar stability to prevent injury, therefore the diaphragm will exert an upward tension while the psoas major exerts a downward force, this is a balance between static and dynamic restraints driven by a co-contraction of small segmental stabilisers and large abdominal musculature. If our diaphragm is not functioning properly our body will then pressure the other musculature making them work harder which in turn can lead to a less stable environment, which over time can lead to dysfunction and or pain.

Our bodies almost always naturally adapt to our environments, in cases of lower back pain we can easily see altered stability and mobility of the diaphragm. When diaphragmatic contraction decreases, the crus tendon can increase in tension, due to its attachment’s this can result in an increased tension and reduced motion around lumbar segments (L1-L3), with this restraint the lower segments (L4-L5) will become hypermobile and therefore less stable, to prevent anterior glide of these segments the nervous system will shorten the illio-lumbar ligaments and therefore restrict motion at sacroiliac joints (SIJ). The end result is a partially fixated and dynamically unstable lumbar spine, increasing likelihood of pain in these areas due to increased load and movement dysfunction.

How can we help? Our therapists are educated in certain release techniques such as a diaphragm pull or release from under the rib cage. We can also educate our patients on correct breathing habits ; in conjunction with manual manipulation of the spine, we can reset and relearn certain poor habits and replace them with better ones that alleviate and avoid pain. Sometimes the smallest things make the biggest change. Overall, you can expect a reduction in neck, mid-back and low-back pain as well as improved performance whether in sports or in life.

Paul Morana